If you or someone you love has diabetes, you’ve likely heard of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)—but what is HHS in diabetes, and why should you care? Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) is a rare but extremely dangerous complication of type 2 diabetes that can lead to coma or even death if not treated immediately. Unlike DKA, HHS often sneaks up slowly, making it easy to miss until it’s too late. In this guide, we’ll break down everything you need to know—from early warning signs to emergency treatment—so you’re prepared, informed, and empowered.

What Exactly Is HHS in Diabetes?

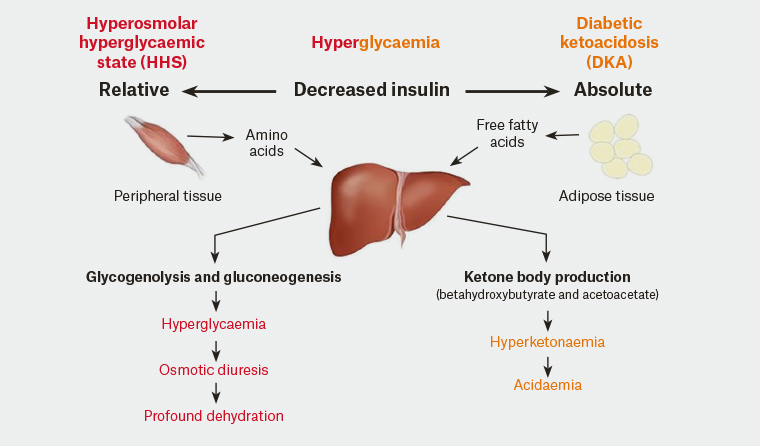

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) is a serious condition that occurs when blood sugar levels rise to dangerously high levels—typically above 600 mg/dL—without significant ketone production. It’s most common in older adults with type 2 diabetes, especially those who may not be managing their condition well or are unaware they have diabetes.

Unlike diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), which involves high ketones and acid buildup, HHS is characterized by severe dehydration and extreme hyperglycemia without significant acidosis. This makes it harder to detect early, as symptoms can mimic general illness or fatigue.

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), HHS has a mortality rate of 10–20%, significantly higher than DKA, largely because it affects older, more vulnerable populations.

💡 Key Fact: HHS accounts for only 1% of all diabetic emergencies—but it’s responsible for a disproportionate number of diabetes-related deaths.

What Causes HHS in People with Diabetes?

HHS usually develops over days or even weeks, often triggered by an underlying illness or event that spikes blood sugar while reducing fluid intake. Common causes include:

- Infections (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infections)

- Heart attack or stroke

- Medications that affect blood sugar (e.g., corticosteroids, diuretics)

- Inadequate insulin or diabetes medication

- Limited access to water (common in elderly or disabled individuals)

The body tries to eliminate excess glucose through urine, leading to massive fluid loss. Without enough water intake, dehydration worsens, blood becomes thicker, and the brain and organs begin to suffer.

Signs and Symptoms of HHS: Don’t Ignore These Red Flags

Early symptoms of HHS can be subtle, but they escalate quickly. Watch for:

- Extreme thirst (though this may fade as dehydration worsens)

- Dry mouth and skin

- Frequent urination (early on)

- Weakness or fatigue

- Confusion or altered mental state

- Vision changes

- Seizures or coma (in advanced stages)

⚠️ Critical Insight: Mental confusion is often the first sign family members notice. If your loved one with diabetes seems “off” or unusually drowsy, check their blood sugar immediately.

HHS vs. DKA: Key Differences Every Patient Should Know

Many confuse HHS with Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA). While both are diabetic emergencies, they differ significantly:

| Typical Diabetes Type | Type 2 | Type 1 (but can occur in type 2) |

| Blood Glucose Level | >600 mg/dL | Usually 250–600 mg/dL |

| Ketones | Minimal or absent | High |

| Onset | Gradual (days to weeks) | Rapid (hours) |

| pH Level | Normal or slightly low | Acidic (<7.3) |

| Common Age Group | Older adults (60+) | Younger patients |

Understanding these differences helps healthcare providers choose the right treatment—and could save precious time in an emergency.

For more on metabolic emergencies in diabetes, see this authoritative overview on Wikipedia .

How Is HHS Diagnosed?

Doctors diagnose HHS based on blood tests showing:

- Blood glucose >600 mg/dL

- Serum osmolality >320 mOsm/kg

- Absence of significant ketosis

- Normal or near-normal blood pH (>7.3)

Additional tests may include:

- Electrolyte panel (sodium, potassium)

- Kidney function tests

- Infection screening (urine, blood cultures)

Early diagnosis is critical—delays increase the risk of stroke, heart attack, or permanent neurological damage.

Step-by-Step Emergency Treatment for HHS

HHS requires hospitalization, often in an ICU. Treatment follows a strict protocol to avoid complications like brain swelling:

- Fluid Replacement:

- Start with 1–2 liters of 0.9% saline over the first hour.

- Total fluid deficit can be 8–12 liters—replaced gradually over 24–48 hours.

- Goal: Restore circulation and kidney function without causing cerebral edema.

- Insulin Therapy:

- Begin IV insulin infusion (typically 0.1 units/kg/hour) after initial fluid resuscitation.

- Blood glucose should drop by 50–75 mg/dL per hour—not too fast!

- Electrolyte Management:

- Monitor potassium closely—hypokalemia is common once insulin starts.

- Replace potassium if levels fall below 5.3 mEq/L.

- Treat Underlying Cause:

- Administer antibiotics for infection.

- Manage heart conditions or other triggers.

- Continuous Monitoring:

- Hourly glucose checks.

- Neurological assessments every 2–4 hours.

🩺 Real-World Example: A 2022 case study in Diabetes Care reported a 72-year-old man admitted with confusion and glucose of 980 mg/dL. After 36 hours of IV fluids and insulin, he recovered fully—highlighting the importance of rapid intervention.

Can HHS Be Prevented?

Yes—most HHS cases are preventable with proactive diabetes care:

- Check blood sugar regularly, especially during illness.

- Never skip diabetes medications—even if you’re not eating.

- Stay hydrated: Aim for 6–8 glasses of water daily, more if sick or hot.

- Have a sick-day plan: Know when to call your doctor (e.g., glucose >300 mg/dL for 2+ readings).

- Educate caregivers: Ensure family or home aides recognize early signs.

The ADA recommends that all type 2 diabetics over 60 keep a glucose meter and emergency contact list easily accessible.

FAQ: Common Questions About HHS in Diabetes

Q1: Can HHS happen to people with type 1 diabetes?

While rare, yes—especially in older adults with long-standing type 1 diabetes who still produce some insulin. However, over 95% of HHS cases occur in type 2 diabetes.

Q2: How fast does HHS develop?

Symptoms can appear over 24–72 hours, but the metabolic imbalance may build over several days or weeks. This slow onset is why it’s often missed.

Q3: Is HHS fatal?

Unfortunately, yes—if untreated. Mortality rates range from 10% to 20%, often due to underlying conditions like heart disease or sepsis.

Q4: What should I do if I suspect HHS?

Go to the ER immediately. Do not wait. Call 911 if the person is confused, lethargic, or unconscious. Bring their diabetes supplies and medication list.

Q5: Can drinking water prevent HHS?

Hydration helps, but it’s not enough alone. You still need proper insulin or medication to lower blood sugar. However, dehydration is a major trigger, so water is essential—especially when sick.

Q6: How is HHS different from regular high blood sugar?

“Regular” high blood sugar (e.g., 200–300 mg/dL) may cause fatigue or thirst but isn’t immediately life-threatening. HHS involves extreme hyperglycemia (>600 mg/dL) + dehydration + altered mental status—a true medical emergency.

Conclusion: Knowledge Saves Lives

Understanding what is HHS in diabetes isn’t just academic—it’s a matter of life and death. With early recognition, prompt treatment, and consistent diabetes management, HHS can be avoided or successfully treated. If you care for someone with type 2 diabetes, share this guide. Print the symptom checklist. Talk to their doctor about a sick-day plan.

👉 Your next step: Bookmark this page, share it on Facebook or WhatsApp with family caregivers, and check your loved one’s blood sugar today. A few minutes could prevent a tragedy.

Stay informed. Stay prepared. Stay safe.

Leave a Reply